States Veer Toward Extended Producer Responsibility Laws

Laws mandating extended producer responsibility for packaging are gaining momentum

On Jan. 8, New York State Senator Todd Kaminsky introduced S1185B, a bill establishing the extended producer responsibility (EPR) act, in the state legislature. The bill would require product producers to develop and implement strategies to promote recycling and the reuse and recovery of packaging and paper products. It is on the senate’s floor calendar and joins similar bills under consideration in other states.

Similar bills have routinely been introduced for some time and failed. Lately, however, the plastics industry recognizes the benefit of helping to craft EPR legislation that is in the interest of its members and producers are coming to the table and collaborating on such proposals.

Two factors driving this movement include the continuing growth of flexible packaging and the desire of consumers to recycle and reuse packaging. Industry and producers are also keenly aware of state and local bans on retail T-shirt bags that are primarily targeted at litter reduction but also reflect a lack of collection and reuse infrastructure.

Additionally, many private and municipal recycling programs lost a major market when China stopped importing recyclables in 2018 and seek to regain some of this business via collection and reuse initiatives. The COVID-19 pandemic has stretched state budgets, and there is a lack of political will for tax increases to fund government collection and recycling programs.

The sum of all these concerns is EPR legislation.

“This perfect storm is also the perfect opportunity to overhaul the U.S. recycling system to provide a long-term sustainable approach for all packaging,” says Alison Keane, president and chief executive officer of the Flexible Packaging Association (FPA). “We need food sterility. We need PPE (personal protective equipment).” Thanks to the pandemic, consumers and policy makers understand this and recognize the benefits plastics bring to both. “We are seeing a recognition that [many recyclable products are] necessary, but let’s work on a system so, at the end of life, [products] get … circularity.”

“It’s long overdue,” says Conor Carlin, SPE’s vice president of sustainability and managing director of thermoforming equipment manufacturer Illig North America. “I think industry has pushed back against legislation maybe once too often.”

“Has the time come?” asks Dan Felton, executive director of Ameripen, an organization focused on U.S. public policy for the packaging industry. “Some people say Ameripen was founded to oppose EPR. Ameripen had always opposed EPR bills for packaging,” he concedes. “We have shifted in that thinking. If industry has to look at legislation that puts responsibility on industry to help finance the system, then what ideally might that look like? We’ve come around to saying, ‘We could support bills if they had this.’ Or, at minimum, we are finding ourselves in a position where there are some bills we don’t have to oppose. That’s a significant shift,” Felton says. “The industry recognizes the time is here and we’re going to sit down at the table and have real conversations.”

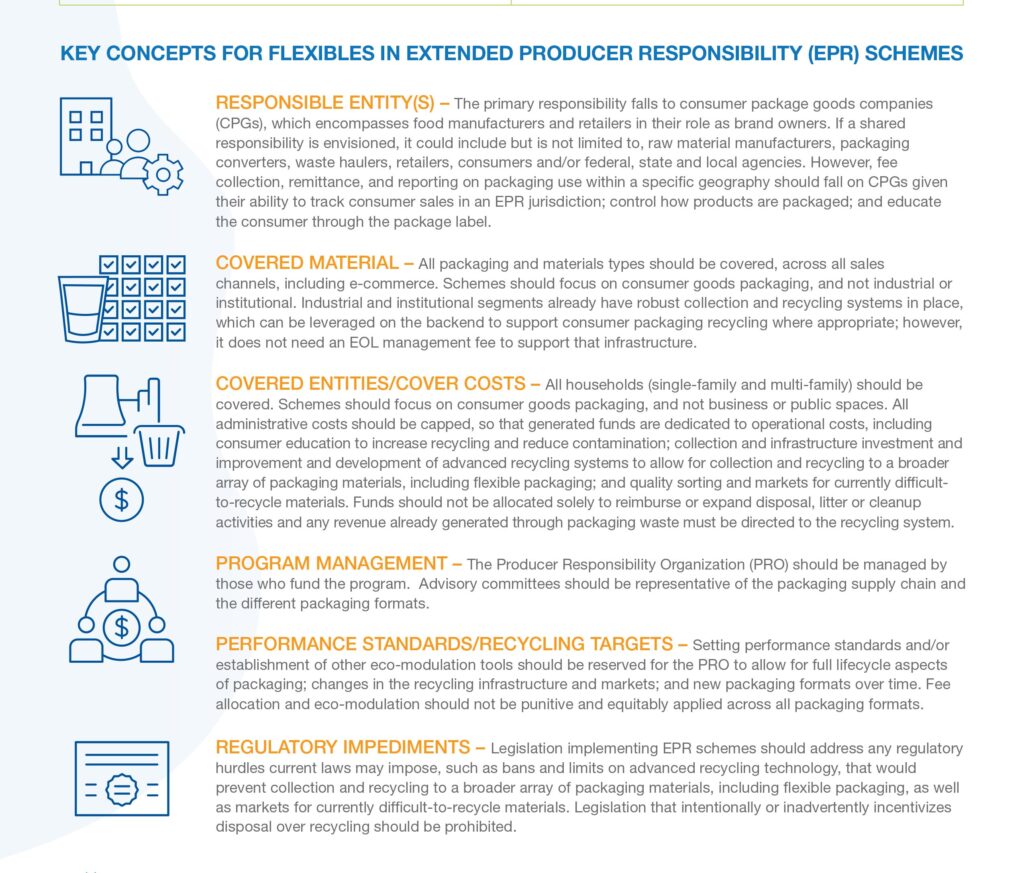

Infographic details EPR rules and responsibilities for packaging suppliers. Courtesy of Flexible Packaging Association

Those conversations grew when the FPA and the Product Stewardship Institute (PSI) agreed upon legislative elements for a plastics and paper packaging EPR bill. The FPA/PSI dialogue marked the first time in the U.S. that producers of flexible packaging, state and local government agencies, environmental groups and recyclers collaborated to develop a legislative framework for packaging EPR.

“We convene stakeholders,” says Scott Cassel, founder and CEO of PSI. “We bring different groups together to figure out what the joint problem is, what the joint goals are, what the barriers are toward achieving those goals, and what the solutions are.”

Keane previously worked with Cassel on the PaintCare EPR program in her former role with the American Coatings Association, which paved the way for her to initiate the FPA’s dialogue with PSI.

“PSI is the only organization bringing solid waste officials and professionals from all over the U.S. to the table at one time,” she says. “That allows associate members like the FPA, as well as others in the supply chain, to have a one-stop shop to discuss the issue. My perspective enabled me to get on board with EPR a little faster.”

“PSI’s process builds trust between different stakeholders,” says Sydney Harris, senior associate of policy and programs at the institute. “But I also think when there is EPR for a given product in place, that is industry’s opportunity to earn the trust of other stakeholders by effectively implementing the program. And let’s be honest, there is some lack of trust in packaging because the industry has not been involved much in the conversation.”

The New York bill shows the potential of that process and of the model derived from the FPA dialogue towards crafting legislation. PSI worked with the New York Product Stewardship Council from day one, walking the organization through the institute’s model and bringing other groups to the table to express concerns.

“Ameripen is intimately involved in the New York bill,” says Felton. “We’re meeting regularly with our members and Sen. Kaminsky’s staff. Elements of the bill reflect conversations we’ve had with stakeholders.”

Nevertheless, Keane cites concerns.

“We’re opposing the New York bill, but we’re closer to not opposing it,” she says. “If you’re going to have an EPR system, we want to ensure that the brands and producers that are establishing the producer responsibility organization (PRO) don’t just have financial responsibility, but some operational control. The current system we’ve had for the last 30 years clearly isn’t working; otherwise, we wouldn’t be seeing EPR proposals.

“It’s a delicate balance to stabilize current infrastructure while also making the system more efficient and investing in new infrastructure and technology,” Keane continues. “We need to ensure not just what’s recyclable today, but what could be recyclable in the future gets recycled. If you don’t give some control to the PRO to make it happen, you’re just raising a whole bunch of money and continuing the status quo, and we wouldn’t be having this conversation if the status quo was adequate. I do not believe, in its current form, that [the bill] will provide the sea change we need, as it is too heavily focused on supporting the current infrastructure and not what recycling in the U.S. needs to be.”

“This bill seems thoughtful,” says Carlin. “If you collect funds, who manages and distributes them? A lot of people in the private sector are skeptical of states running those types of programs. They think people might have agendas. There’s a lot of anti-plastics sentiment that could creep in that they could use the funds for something other than recycling infrastructure. The flip side is the states know if the bills don’t have teeth, industry will water them down as much as possible because that’s what they’ve done in the past. The PRO position is the right approach, but it needs to be balanced so everyone is happy. We can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. If the New York bill can be collaborative and not adversarial between the legislative and private sectors, it’ll be a good model to follow.”

To date, PSI has helped pass 120 EPR laws on 14 products across 33 states. Still, all stakeholders recognize that, while state legislation will inevitably occur first, a federal EPR law (such as the Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act, based on PSI’s model and reintroduced in congress this year) is the ultimate end game.

“It may take a critical mass of state laws being in place first,” says Harris.

And the state laws won’t be uniform, Carlin remarks. “It’s going to be a patchwork.”

“We need investment in sustainable systems and a 50-state approach protecting the status quo will not get us there,” Keane says. “If done right it will enable real change, which means investment in collection and recycling infrastructure and end-market development for all packaging materials. The federal government is going to need to step in and provide an overview to help harmonize [the law]. It will be at best a challenging commerce issue. We don’t label, make packaging or sell products for individual states. There is a real need for structure at the federal level.”

“Sometime in 2022, I would expect there to be 2 to 5 states with EPR packaging laws in place,” says Felton. “That’s why we are so keen to get as much right in the first bill that’s enacted into law. These bills are vastly different from state to state. Ameripen has always argued that we want something done at the federal level to simplify things for producers.”

All stakeholders agree that the collaborative approach the plastics industry has adopted is not just the right tactic, but the only viable one.

“It is inevitable [EPR] will happen because it’s the best way of managing waste, but it’s an evolution,” says Cassel. “Any transition will take time. The more collaborative we can be, the less painful it will be for all stakeholders.”

“The whole supply chain needs to solve this,” says Keane. “It’s not just going to be one state or one piece of legislation.”

“We shouldn’t be so cynical to say it’ll all blow up,” notes Carlin. “We have to be optimistic. The future is not condemned to look like the past.”