Additive Formulations Target Evolving End-Use Needs

Additive suppliers fine-tune grades that enhance recycled polymers, product aesthetics and shelf life

From stabilizers to odor reduction and aesthetics that appeal on multiple levels to consumers, developments in colors and additives have continued apace despite the pandemic—particularly the demand for germ- and virus-killing materials.

“We have been busy all along,” says Robert Nunez, director of new business development in polymers at Baerlocher USA of Cincinnati.

The company, a major supplier of stabilizers and lubricants, has seen demand increase for its Baeropol resin stabilizers, which are geared toward producing better performing recycled polymers.

“Right now, we’re laser focused on packaging because that is the segment that has the most urgent need for change and improved quality,” Nunez says. “The closer you are to the consumer, the more pressure you have to improve your sustainability image. Consumers buying shampoo, milk or other items in the supermarket have regular contact with a brand versus those buying a car or refrigerator every so many years. We concentrate fully on all segments, but packaging is under much more pressure.”

Baerlocher stabilizers, which can feature three chemistries on one package—antioxidants, antiacids and lubricants—are developed through engagement across the value chain, from petrochemical companies to brand owners, Nunez explains.

Given some corporate goals for greater use of post-consumer recycled (PCR) materials as soon as 2025, “this may be one of the best moments for PCR development, as there is a lot of demand,” he remarks. “There is a struggle with supplying really good-quality PCR. Then you have the converters who want to satisfy the brand owners; they need higher-quality PCR as well. It’s a good environment in which to develop not only material solutions but applications.”

In flexible packaging, Baerlocher sees customers having success with using its additives to reduce gels. “We’re able to minimize crosslinking during the melt filtration process. If you clean and process PCR properly and go through melt filtration at the recycling stage, typically if you don’t have any stabilization, you are degrading the polymer—maybe you crosslink the polymer. You create more gels than there were before. Nevertheless, the polymer is cleaner in terms of organic or inorganic things. Filters do a good job cleaning but if you don’t protect your polymer, you get more trouble. Customers have been able to reduce gel counts by using our technology.”

With fewer gels, he adds, “you can consider downgauging; if you’re running a blown film line, maybe you don’t have so many shutdowns due to gels, which are very typical.”

Meanwhile, Baerlocher is assessing the effectiveness of its stabilizer packages in blow molding. Baeropol T-Blend 1111 TX employs the company’s resin stabilization technology to enhance PCR performance in extrusion blow molding. Recent data indicate that the blend, which is added directly during recycling, can reduce flash waste by 23 percent in bottles and achieves higher melt strength and top load strength versus traditional stabilizer blends at 0.3 percent loading.

“Imagine that you have a stabilization package that you use with high-density polyethylene,” Nunez says. “We are going into more detail about exactly what value the converter can get—not just from material but the application. For instance, when we do application development work, we determine if parison control is much better. If it is, what does it mean in terms of the final materials? In blends of PCR versus virgin? What does it mean in terms of final properties at the barrel that will make the brand owner happier, meet requirements or allow someone to say now we can downgauge? Before we couldn’t do that. It’s an exciting time.”

Stability, Safety and Odors

One of the thorniest issues to be addressed with colors and additives is reconciling consumers’ needs for transparency and safety in their products with brand owners’ needs to create products “that use plastics more efficiently, contain higher recycled content and won’t ultimately end up in landfill, waterways or incineration,” says Doreen Becker, sustainability director at Ampacet Corp. and SPE Color and Appearance Division (CAD) board member. “These two sets of requirements are quite different and sometimes in direct opposition to each other.”

Packaging materials and designs need improved properties, as consumers pressure brand owners for greater quality and sustainability. Shown are test bottles in Baerlocher lab.

Among the hurdles in bridging those expectations, Becker explains, is the fact that “the chain of custody for recycled materials is almost impossible to track. Also, mechanical recycling does not remove many of the additives and contaminants that were present in the plastic in its previous life. Some of these contaminants can be covered up or partially removed. Others cannot.”

As the world works to navigate away from the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in antimicrobial additives is surging. Of course, antiviral additives function differently than antibacterials.

“It is true that antiviral additives will kill certain viruses under certain conditions, but that doesn’t mean that consumers will be protected from all viruses all the time,” Becker cautions. “Also, antibacterial additives kill bacteria such as E. coli but are not designed to kill viruses or every type of bacteria. These antimicrobial additives can help reduce viral and bacterial illnesses and transmission but won’t eliminate them entirely.”

Ultimately, “Consumers want safe and clean products, and some are willing to pay more for these additives if they think it will keep their families healthy.”

In terms of challenges in color use, Becker notes that “some brands want to take color out of their designs to keep recycled plastics more transparent and lighter in appearance. However, there are other additives such as adhesives that contaminate the recycling stream and cause recyclate to appear yellowish or greenish. There are a number of color solutions to help shift that color back to a more desirable shade while also adding clarity to finished products.”

Carbon black colorants, moreover, “interfere with the polymer sorting process in mechanical recycling, so the resulting unidentified polymers are sent to landfill or incinerated. The good news is that there are now near-IR transparent blacks that will not interfere with sorting. We are learning that some colorants help stabilize recycled plastics so they can be used at higher concentrations and have better physical properties than recycled plastics that don’t contain color. We also see a number of ‘cooler’ colors that help reduce the temperatures of products such as roofing tiles and automotive interiors and lessen the need for air conditioning or other energy-intensive cooling processes.”

Meanwhile, odor-reducing additives are generating increased demand due to the exposure of commingled plastics to a range of unknown contaminants. “A large percentage of recycled plastics have an off-odor,” Becker notes. “This is important to consumers who don’t want their finished goods to smell dirty or contaminate the contents of a recycled plastics package.”

Transparent colors are also gaining ground, she continues, because they “allow consumers to see through the plastic and engender trust and confidence in the product. Bright whites, strong blues and fresh fruit colors are important because they convey a sense of cleanliness (white), strength and confidence (blue) as well as an energetic, healthy and fun optimism (fruit colors).”

Dairy Brands Look to PET

Consumer desires for sustainable packaging that complements healthy beverages spotlight Penn Color’s pennaholt light-blocking masterbatch technology.

Pennaholt “gives brands the flexibility to dial-in package opacity, light-blocking properties and high whiteness while eliminating titanium dioxide (TiO2),” says Jim Wagner, marketing communications manager at the Doylestown, Pa., company. “Dairy brands are adopting polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles which are light, unbreakable, resealable and hygienic, while offering freedom to design differentiated shapes and decorations.”

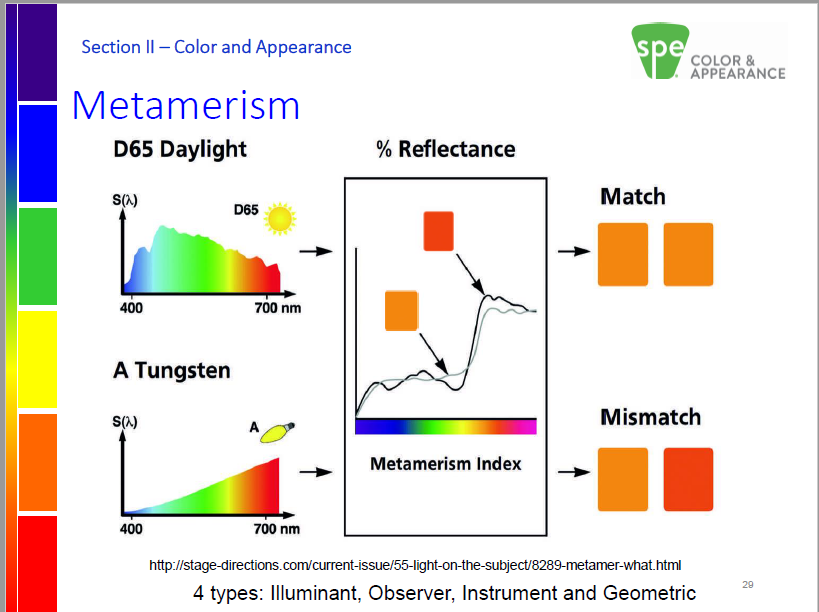

Metamerism is when two colors identical under one light source appear as different colors under another light source. Samples viewed under Illuminant A, a red-rich incandescent illumination, and then under a blue-rich spectral power distribution will change color, as one appears different than the other. In this image the D65 daylight source results in a match on the right—the two orange blocks. The A tungsten light results in a color mismatch, shown by orange and red blocks at bottom right. Courtesy of CAD RETEC/Jack Ladson

The patented technology, he adds, enables “high opacity and premium whiteness PET bottles,” which are increasingly sought after as consumers shun carbonated soft drinks in favor of natural and nutritious options such as milk and other dairy-based beverages. Retail buyers also want packaging that ensures product shelf life while helping to achieve sustainability goals.

Transparent PET bottles have a light transmission rate of 90 percent. White PET bottles with pennaholt typically have a light transmission rate of less than 0.5 percent at 550 nm, which is the most harmful wavelength for white milk, Wagner notes. In special cases, pennaholt not only reduces light transmission to below 0.2 percent, but extends protection to longer wavelengths.”

Being formulated to support circularity, pennaholt “supports bottle-to-bottle recycling in the dedicated white or non-clear recycling stream,” Wagner says. “All pennaholt components are specifically chosen for purity, high thermal stability and high molecular weight. This minimizes the risk of non-intentionally added substances in PET packages made with pennaholt as they undergo multiple recycling cycles and PET packages contain more recycled PET content.”

Furthermore, because pennaholt is formulated with low or no TiO2, bottles “may be recycled in the non-clear PET stream without the degradation that occurs with conventional formulations,” Wagner says. “Brands also do not have to deal with uncertainty related to consumer perception and to how European regulators interpret waste directives for packages with TiO2.

Seeing and Believing

Formulating colors that resolve visual differences caused by different light sources is an important area of development and the bailiwick of Jack Ladson, owner of Color Science Consultancy, Frederick, Md., a CAD board member.

In particular, the explosion in use of LED lighting and mass replacement of incandescent and fluorescent lights has had far-reaching impact on color formulators and brand owners attempting to match previous color performance and end-user expectations. Unfortunately, Ladson notes, the science of properly rendering color is so little understood industrywide that the challenge is compounded.

According to the Color Rendering Index created by the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST), the ideal illuminant—outdoor sun—is the basis upon which lighting scenarios are compared. The core issue, Ladson says, is spectral power distribution: the amount of energy per unit of wavelength over the visible spectrum.

“LEDs are constructed in such a manner to produce acceptable light levels to us, but they do not have a spectral power distribution that we have ever seen before. As a result, the mathematics developed for the analysis of incandescent and fluorescent illumination does not work. This and the fact that development of LEDs is at its beginning stage means there are no standards.”

Big-box retailers drive the choice of LEDs, Ladson says, by choosing specific models of LEDs and company-specific lighting booths that illuminate sample products according to strict, proprietary specifications. From a standardization standpoint and user perspective, “this is an absolute nightmare.”

Why should end-users—i.e., brand owners and color suppliers—know or care about this?

“The problem is that a manufacturer of colored goods needs to be extraordinarily careful about the selection and use of LED lighting booths—and they need to become well informed and to understand the state of the art and the customer they are serving,” Ladson says.

The core phenomenon of concern is metamerism, in which two colors identical under one light source appear as different colors under another light source. If one views a set of samples under Illuminant A, which is red-rich incandescent illumination, and switches to a blue-rich spectral power distribution, such as D6500 or daylight, “a metameric sample pair is going to change color, one different than the other,” he explains.

In practical terms, “Imagine walking into a store and buying clothing, then walking out of the store and finding that your pants are a different color than your jacket.”

Ultimately, Ladson concludes, “It’s the Wild West out there.” Is there a solution for end-users?

“Users have to approach this with caution and an understanding of what the specifications are for which they are supplying products; they need to understand what kind of LED illumination is employed.” Top suppliers design innovative new pigments that “have some property that is of interest to a user,” such as stronger hue, greater brightness, or more weather or mechanical reliability.

“When people talk about these subjects at SPE meetings, folks sit up and pay attention,” Ladson says. The issue “creates a lot of anxiety in people who use light booths to manufacture products. The color appearance of an item is what we’re trying to control. Color is an integral part of our perception, but it’s not that alone; it is also the appearance attribute. Two surfaces with the same color but a different surface texture will have a different color appearance.”

Considering the significant challenges facing pigment and material engineers and suppliers, Ladson’s mission with his training is to foster a “tremendous increase in the efficiency and development of colorants and quality of the end product.” Greater understanding of color science, he adds, will “help people get to market faster and produce better products—ones that are more aligned with customers’ needs.”